Agentic AI with DuckDB turns natural language queries for analytics from a nice idea into something you can actually run today. Many users don’t want to think in joins, window functions, or aggregate clauses — they just want answers. Here I’ll walk through how I use smolagents as an agent framework on top of DuckDB, so that the agent writes the SQL, executes it, and explains the result:

-

User asks:

“Which products generate the highest sales for older customers?” -

An agent:

-

understands the question,

-

turns it into a DuckDB-compatible SQL query,

-

executes it,

-

and summarizes the result in English.

-

-

The user gets both: the explanation and the underlying SQL and result table.

Technically, I build this with:

-

smolagents as the agent framework, and

-

DuckDB as the in-process analytical database engine.

The full notebook 02_Cleansing_DuckDB.ipynb is in my GitHub repo KINAVIGATOR2025, ready for Colab

In this article, I’ll walk through the concepts and code including a query. The notebook contains the full workng code including also a two table join.

What is Agentic AI – and why?

LLMs are great at generating text. But in a data architecture context, I rarely just want “text”. I want a system that:

-

understands a goal (“Segment customers by behavior”, “Highlight data quality issues”),

-

creates and refines a plan,

-

calls different tools (SQL engines, Python code, APIs) to get real work done,

-

inspects intermediate results and corrects itself,

-

and produces a transparent, explainable outcome.

That’s what I mean by Agentic AI:

An LLM that acts as an agent with a goal, a toolkit, and an iterative loop of reasoning and acting – not just a one-shot text generator.

Frameworks like smolagents formalize this pattern. An agent is:

-

backed by a language model,

-

equipped with a set of tools (Python functions with clear contracts),

-

guided by a system prompt and constraints,

-

and usually runs in a loop: think → act (tool call) → observe → think again, until it can answer.

smolagents focuses on a very small, transparent core: the logic for agents fits in roughly a thousand lines of code and is optimized for simplicity and inspection.

Why should I care as a data architect?

-

Self-service with guardrails

Business users ask questions in natural language. The agent writes SQL, but we keep control over which tables and tools it can touch. -

Reuse of an existing stack

Agentic AI doesn’t replace DuckDB, warehouses, or pipelines. It orchestrates them. DuckDB stays the analytical workhorse; the agent is the “query brain”. -

Explainability by design

With the right verbosity settings, I can inspect all intermediate steps: which SQL was generated, what the result looked like, and how the final conclusion was derived.

Components: smolagents and DuckDB

smolagents

smolagents is a lightweight, open-source Python library from Hugging Face for building agents. Key characteristics:

-

Simplicity: The abstractions are intentionally minimal. An agent, some tools, a model. Not a full-blown orchestration platform.

-

Code-first agents: With

CodeAgent, the agent writes Python code that calls tools. This is expressive and easy to reason about. -

Tool integration: Tools are just Python functions decorated with

@tooland a clear docstring that tells the LLM how to use them.

This makes smolagents a good fit for notebooks and exploratory data work: I can see exactly what happens and change it quickly.

DuckDB

DuckDB is an in-process SQL OLAP database management system. It runs embedded in your application or notebook, not as a separate server. Key aspects for this use case:

-

Designed for analytics: Optimized for OLAP workloads – scans, aggregations, joins – rather than transactional OLTP.

-

In-process: No external service; a simple Python import and a connection object are enough.

-

Columnar, vectorized engine: Efficient for analytical queries over reasonably large data on a single machine.

-

Good ecosystem fit: Direct support for Parquet, CSV, JSON, data lake formats, and integration with Python and R.

In my previous post I use DuckDB inside Jupyter/Colab as a flexible analytics engine. Here, it becomes the SQL backend for the agent.

Example: from natural language to a two-table join

In the notebook 02_Cleansing_DuckDB.ipynb, I set up a small, illustrative schema with two core tables:

-

customer– one row per customer, with demographics. -

sale– one row per sale, including product and amount.

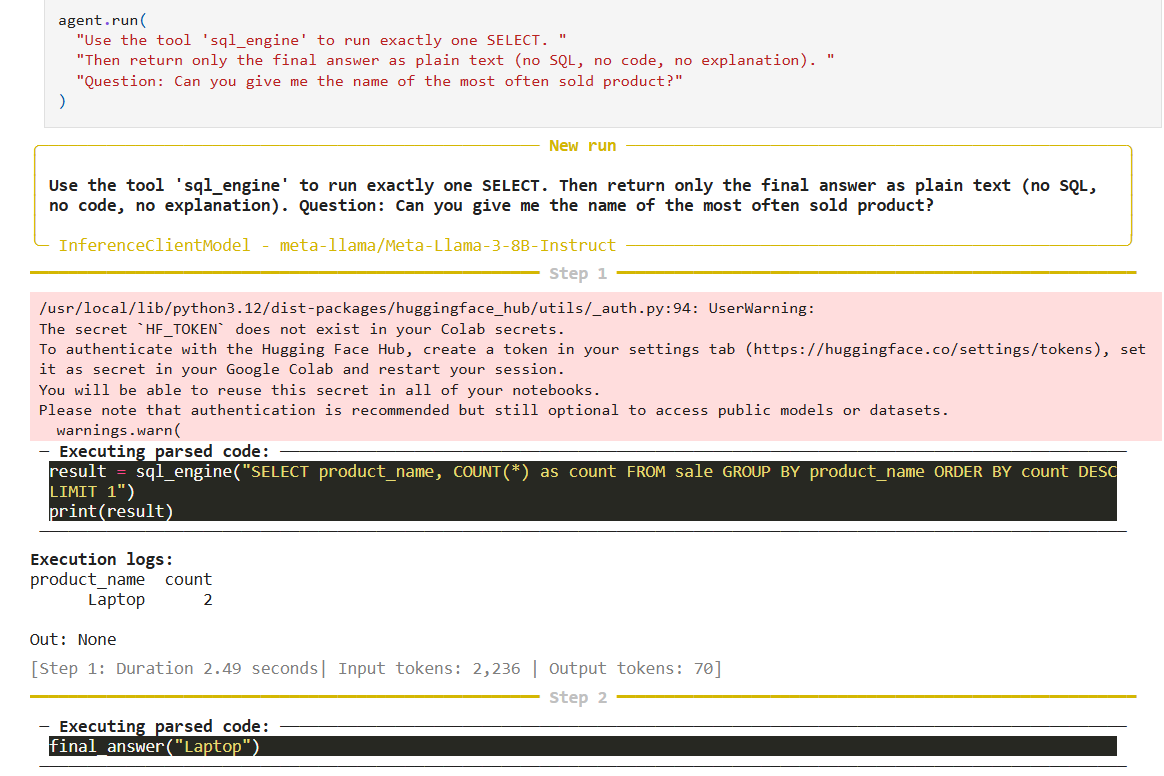

The picture show an example output from an agent run. The user asks “Question: Can you give me the name of the most often sold product?” in natural language, then the agent logs into Hugging Face for access to an LLM (you can use LLMs in other locations, too) , creates an SQL, executes it and returns the result.

Let’s walk through the pipeline from setup to a joined query.

Step 1: Set up DuckDB and demo tables

First, I create an in-memory DuckDB database for the demo (in a real project, this could be e.g. any other database or a table format like Delta / Iceberg).

Note: I show simplified, self-contained examples here; the notebook contains the full, runnable version.

import duckdb # In-memory DuckDB for the demo

con = duckdb.connect(database=":memory:")

con.execute(""" CREATE TABLE customer ( customer_id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY,

customer_name VARCHAR,

birthdate DATE ); """)

con.execute(""" CREATE TABLE sale ( sale_id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY,

customer_id INTEGER REFERENCES customer(customer_id),

product_name VARCHAR,

price DOUBLE, sale_date DATE ); """)

# Small demo data

con.execute(""" INSERT INTO customer VALUES (1, 'Alice GmbH', '1960-05-12'),

(2, 'Beta AG', '1985-09-23'),

(3, 'Charlie Ltd', '1948-01-02'); """)

con.execute(""" INSERT INTO sale VALUES (100, 1, 'Product A', 120.0, '2024-01-01'),

(101, 1, 'Product B', 80.0, '2024-01-15'),

(102, 2, 'Product A', 200.0, '2024-02-05'),

(103, 3, 'Product C', 50.0, '2024-02-10'); """)

So far, this is standard DuckDB setup, very similar to what I showed in the DuckDB & JupySQL article.

Step 2: Expose DuckDB as a tool: sql_engine

Now I expose DuckDB as a tool the agent can call. In smolagents, that means decorating a function with @tool and writing a docstring that explains usage and constraints.

from smolagents import tool

@tool

def sql_engine(query: str) -> str:

""" Execute a SQL query against the DuckDB connection.

Rules for the agent:

- The query MUST be valid DuckDB SQL.

- Only SELECT queries are allowed (no INSERT/UPDATE/DELETE/DROP).

- Use this tool to answer questions about the data.

- Return compact result sets; avoid SELECT * with huge tables.

Args:

query (str): SQL query to execute (DuckDB syntax).

Returns:

String table of results or 'OK' for statements without a result set."""

try:

q = query.strip().lower()

if not q.startswith("select"):

return "SQL_ERROR: only SELECT statements are allowed."

df = con.execute(query).df()

if df.empty:

return "Query returned 0 rows."

# Compact textual representation for the LLM return

df.to_string(index=False)

except Exception as e:

return f"SQL_ERROR: {e}" A few observations from a data architecture perspective:

-

The docstring is part of the contract with the LLM. It guides the agent towards safe and appropriate usage.

-

I explicitly restrict the tool to

SELECTstatements here. In a governed environment, this is one of many defense layers. -

I return a text table for the model. If I wanted more structure, I could serialize to JSON, but text usually works well for LLMs.

Step 3: Build a schema description for the agent

The agent needs to know which tables and columns exist, and how they relate. For the demo, I hard-code a simple description; in the notebook, this can be generated from DuckDB’s catalog plus a dictionary of business semantics.

def build_schema_description() -> str:

""" Describe the DuckDB schema in natural language for the agent. """

description = "You can query the following tables:\\n\\n"

description += ( "Table 'customer':\\n"

" Columns:\\n"

" - customer_id: INTEGER, primary key\\n"

" - customer_name: VARCHAR\\n"

" - birthdate: DATE (date of birth)\\n"

" Relationships:\\n"

" - One-to-many with 'sale' via customer_id\\n\\n"

"Table 'sale':\\n"

" Columns:\\n"

" - sale_id: INTEGER, primary key\\n"

" - customer_id: INTEGER, foreign key to customer(customer_id)\\n"

" - product_name: VARCHAR\\n"

" - price: DOUBLE (net sales amount)\\n"

" - sale_date: DATE\\n" )

return description

schema_description = build_schema_description() This is intentionally human-readable. It’s also LLM-readable: the structure (tables, columns, relationships) is simple enough for the model to parse mentally and act on.

Step 4: Construct the smolagents CodeAgent

Now I combine model, tool, and schema into an agent. I use CodeAgent, which lets the agent write Python code that calls tools like sql_engine.

from smolagents import CodeAgent

from smolagents import OpenAIChatModel # or another backend

system_prompt = f""" You are a data exploration assistant for an analytical DuckDB database.

Your job is to answer questions about the data by writing SQL queries.

You have access to the tool `sql_engine` which executes SQL on DuckDB.

Follow these rules:

- Use ONLY the tables and columns in the schema description.

- Prefer clear, simple SQL.

- If one query is enough, use a single SELECT.

- After using the tool, explain the result in clear, concise English.

Schema: {schema_description} """

model = OpenAIChatModel( model="gpt-4.1-mini", # example; configure to your environment )

agent = CodeAgent(

tools=[sql_engine],

model=model,

system_prompt=system_prompt,

max_steps=6, # limit ReAct loops

verbosity="verbose", # show thinking and tool calls in the notebook ) With verbosity="verbose", I get a transparent trace of what the agent does: its reasoning, the SQL it generates, and the tool outputs. For teaching, debugging, and governance, this is extremely helpful.

Step 5: A single-table example – product sales

Let me start with a simple natural language question that only needs the sale table:

“Which products generate the highest total sales amount? Show the top 3.”

question = "Which products generate the highest total sales amount? Show the top 1."

agent.run(question) A reasonable agent will:

-

Plan to aggregate

pricebyproduct_name. -

Generate a SQL query like:

SELECT product_name, SUM(price) AS total_sales

FROM sale

GROUP BY product_name

ORDER BY total_sales DESC

LIMIT 1;

-

Call

sql_enginewith that query. -

Receive a small result table such as:

product_name total_sales

Product A 320

-

And then answer in natural language, e.g.:

Product A has the highest total sales with 320.

This is already valuable: the user never wrote SQL, but can still inspect the exact query and result if they want to.

Summary

Putting a thin agentic AI layer on top of DuckDB changes how people interact with data:

-

They ask questions in natural language, not in SQL.

-

An agent (via smolagents) translates those questions into well-structured, governed DuckDB queries.

-

DuckDB executes them with OLAP-grade performance, right inside the notebook.

-

The agent then explains the results in natural language and, if desired, exposes the SQL and raw tables.

As a data architect, I like this pattern because it:

-

reuses the tools I already trust (DuckDB or any other data store, notebooks, controlled schemas),

-

keeps humans in the loop while automating the tedious query plumbing,

-

and creates a path from small, educational demos (like the two-table join shown here) to serious, governed self-service analytics.

If you want to experiment with this yourself:

-

Start with the DuckDB setup from my earlier post

-

Clone the KINAVIGATOR2025 repository and open the Colab-ready notebook: 02_Cleansing_DuckDB.ipynb

From there, it’s a small and very tangible step to your own agentic AI over DuckDB – tuned to your schemas, your governance model, and your users’ business questions.

It’s easy to start and get first results. But:

- LLMs remain probabilistic.

- Security concerns (e.g., tool usage): current use cases tend to be low-risk and controllable.

- Not every use case requires agents. Déjà Vu Machine Learning: if rules are known, then deterministic solutions are preferable.

- Fast PoC/prototype but then to get it production ready takes professionalization. Déjà Vu Machine Learning: software engineering required until a mature product is achieved.

The article shows a simplistic schema with two tables which is the base for a more complex schema with many tables. Metadata like tables, columns, constraints, and documentation are key.